6 Ianuarie 1536: The Forgotten Scholar: Citlali's Quest to Preserve Aztec Culture Amidst Conquest and Conflict

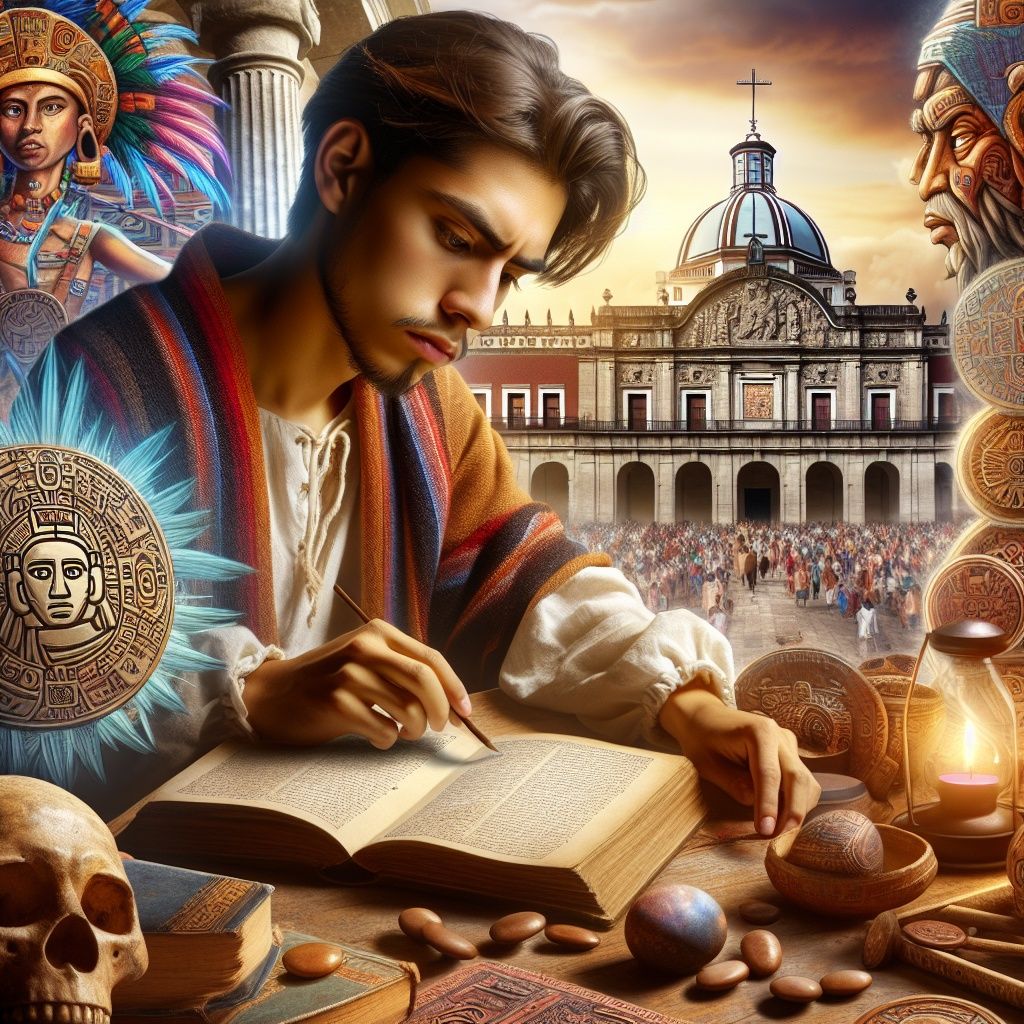

In the vibrant heart of Mexico City, among the history-rich walls of the College of Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, a young indigenous man named Citlali found refuge. Meaning "star" in the Nahuatl language, Citlali was a fitting name for him, for he was to become a shining light in the darkness of an era of change.

It was the year 1550, and Citlali, the son of an Aztec noble, had been one of the few privileged to study at the prestigious college founded by the Franciscans. He had a sharp mind and a thirst for knowledge that could not be quenched. Despite the oppression his people endured, he saw in education a path to blend two worlds: the old one of his ancestors and the new one brought by the conquistadors.

In the classrooms, Citlali learned not only about theology and philosophy but also about the art of translation and interpretation. He was fascinated by how words could unite people separated by a cultural abyss. But his true passion was to study the works of Bernardino de Sahagún, a Franciscan monk who endeavored to record the history and culture of the Aztec people.

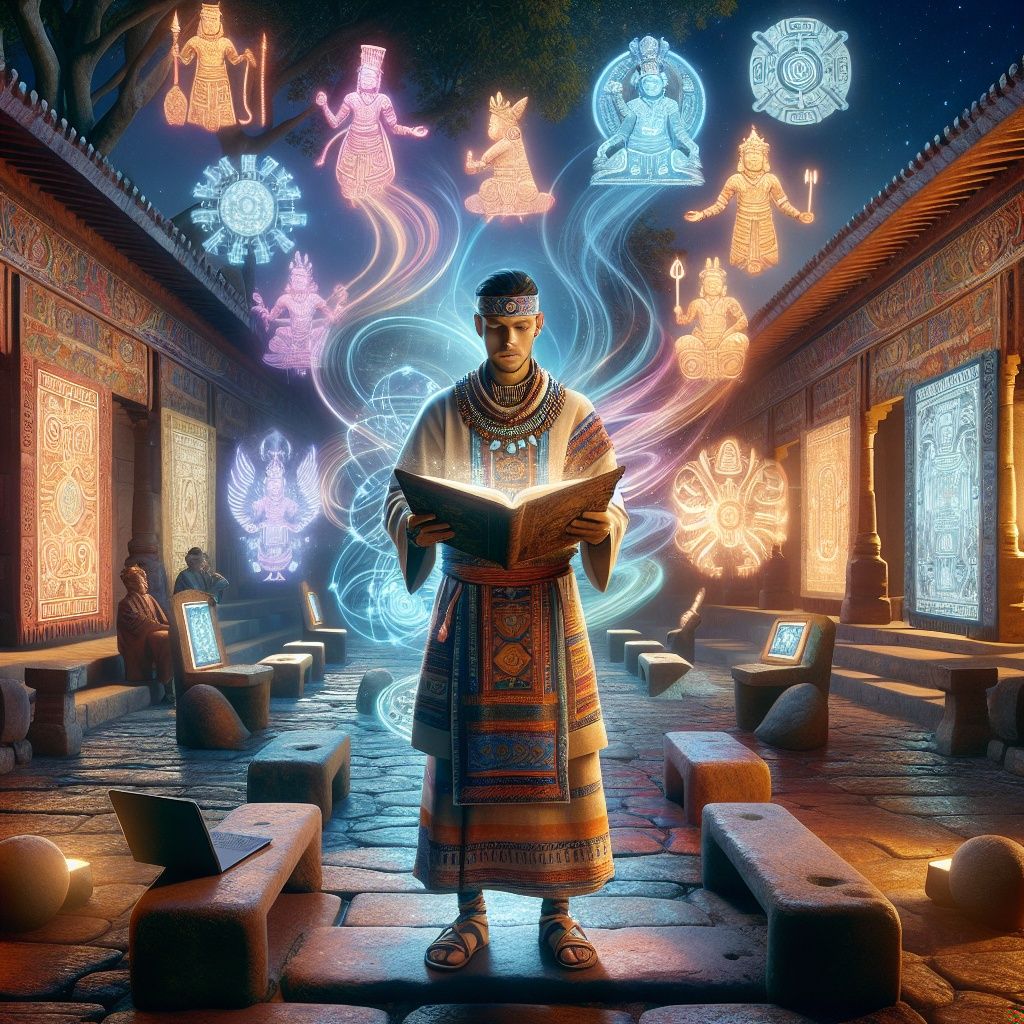

Citlali spent his days and nights trying to find the balance between preserving his indigenous identity and integrating into the new order. He was aware that the college had a dual mission: on one hand, to Christianize the indigenous population, and on the other hand, to create an educated elite that could serve as a bridge between two worlds. One evening, as the full moon rose over the college courtyard, Citlali had a revelation. While reading a manuscript about the Aztec gods, he felt a deep connection with his past. It was as if the voices of his ancestors were speaking to him through the ancient pages, urging him not to forget who he was. At that moment, he understood that his role was not only to be an intermediary between two cultures but also to be a keeper of his people's history and traditions.

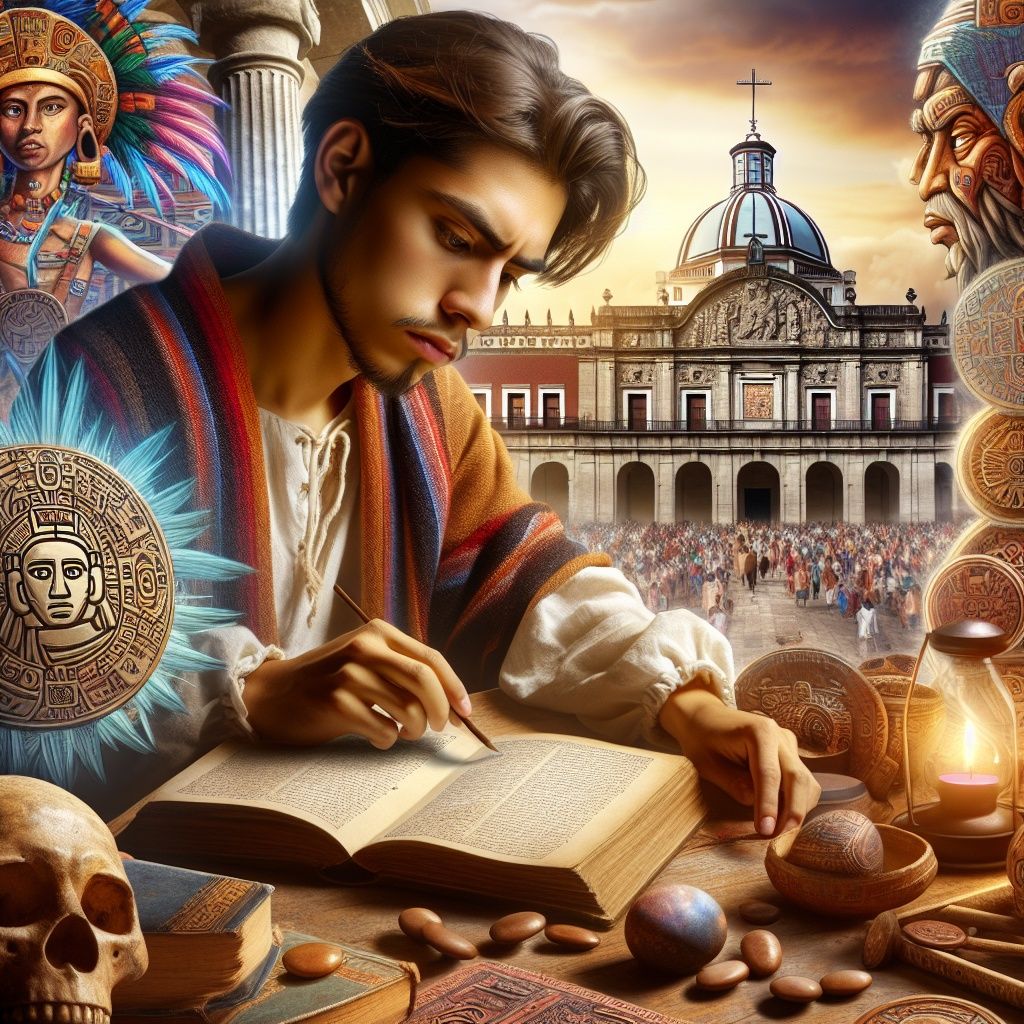

The next day, Citlali began to work alongside Sahagún, helping to transcribe and translate interviews with the Aztec elders. He was a tireless worker, and his work was essential in the creation of a monumental work that preserved for posterity a disappearing culture. But Citlali's success was not viewed favorably by all. Some of his colleagues saw the education of the indigenous as a threat to their power. They began to spread rumors about him, claiming that Citlali was a heretic who wanted to revive the cult of the old Aztec gods. Tensions rose, and the college became a place of conflict between the old and the new, between tradition and progress. Citlali found himself caught in the middle of this whirlwind, struggling to maintain his integrity and to continue the work that he cared for so much. On a fateful night, the college was invaded by soldiers. Citlali was arrested on charges of heresy and brought before an ecclesiastical court. As he stood before the judges, he did not feel fear, but only a deep sadness for the college that had once been a beacon of hope for his people.

The verdict was harsh, but Citlali remained steadfast. He was excommunicated and exiled, but not before hiding the manuscripts he had worked on with Sahagún. He left into exile with a heavy heart, but with the conviction that the truth can never be defeated. Years passed, and the College of Santa Cruz fell into decline. But the story of Citlali survived, as a testimony to the courage and passion of a man who fought to preserve his identity and honor his ancestors. His manuscripts were discovered centuries later, providing the world with a window into a lost culture and reminding us that education and knowledge are the most powerful weapons against oblivion.

Citlali spent his days and nights trying to find the balance between preserving his indigenous identity and integrating into the new order. He was aware that the college had a dual mission: on one hand, to Christianize the indigenous population, and on the other hand, to create an educated elite that could serve as a bridge between two worlds. One evening, as the full moon rose over the college courtyard, Citlali had a revelation. While reading a manuscript about the Aztec gods, he felt a deep connection with his past. It was as if the voices of his ancestors were speaking to him through the ancient pages, urging him not to forget who he was. At that moment, he understood that his role was not only to be an intermediary between two cultures but also to be a keeper of his people's history and traditions.

The next day, Citlali began to work alongside Sahagún, helping to transcribe and translate interviews with the Aztec elders. He was a tireless worker, and his work was essential in the creation of a monumental work that preserved for posterity a disappearing culture. But Citlali's success was not viewed favorably by all. Some of his colleagues saw the education of the indigenous as a threat to their power. They began to spread rumors about him, claiming that Citlali was a heretic who wanted to revive the cult of the old Aztec gods. Tensions rose, and the college became a place of conflict between the old and the new, between tradition and progress. Citlali found himself caught in the middle of this whirlwind, struggling to maintain his integrity and to continue the work that he cared for so much. On a fateful night, the college was invaded by soldiers. Citlali was arrested on charges of heresy and brought before an ecclesiastical court. As he stood before the judges, he did not feel fear, but only a deep sadness for the college that had once been a beacon of hope for his people.

The verdict was harsh, but Citlali remained steadfast. He was excommunicated and exiled, but not before hiding the manuscripts he had worked on with Sahagún. He left into exile with a heavy heart, but with the conviction that the truth can never be defeated. Years passed, and the College of Santa Cruz fell into decline. But the story of Citlali survived, as a testimony to the courage and passion of a man who fought to preserve his identity and honor his ancestors. His manuscripts were discovered centuries later, providing the world with a window into a lost culture and reminding us that education and knowledge are the most powerful weapons against oblivion.

The Santa Cruz College in Tlatelolco, Mexico City, is the first and oldest European higher education institution in the Americas and the first major school for interpreters and translators in the New World. Founded by Franciscans on January 6, 1536, the college significantly impacted the development of an indigenous elite and their contributions to the works of Bernardino de Sahagún. However, the college's subsequent failure had lasting consequences, preventing the formation of an authentic and independent Mexican church. Despite this, the education offered at the college significantly contributed to the Franciscans' efforts to Christianize the natives and to record their history and culture.

Comments

Post a Comment